Contact us

Contact us

Contact us

Contact us

Modern digital technologies, founded on computers, information, and the Internet, have enabled a complete fusion between globally connected cyberspace and the international sphere shaped by human societies. This integration draws on knowledge from the natural sciences to create new tools, thereby contributing to social evolution and the formation of civilization. The introduction of emerging technologies and the flow and sharing of information not only drive remarkable economic and technological progress but also deeply influence human emotions and consciousness.

The Cyber Civilization Research Center defines the civilization brought about by these digital technologies as “Cyber Civilization.”Our research aims to contribute to the design and construction of future societies by fostering a correct understanding of the structure of these technologies.

現代のデジタル技術は、コンピュータと情報、そしてインターネットを基盤とし、グローバルに連結されたサイバー空間と、人間社会が形成する国際空間との完全な融合を実現しました。

この融合は、自然科学の知見を活用し、新たな道具を生み出すことで、社会の進化と文明の形成に寄与しています。新技術の導入と情報の共有・流通は、経済や技術の飛躍的発展を促進すると同時に、人々の心や感情に深い影響を与えています。

サイバー文明研究センターは、こうしたデジタル技術によって生み出された文明を「サイバー文明」として定義し、テクノロジーの構造を正しく理解しながら、未来社会の設計と構築に貢献することを目的とした研究を行います。

*Click here to view the English article. 主催: 慶應義塾大学グローバルリサーチインスティテュート サイバー文明研究センター サイバーセキュリティ研究センター、The MITRE Corporation 日時: 2025年10月28日(火)、29日(水)、30日(木)、31日(金) 9:00~18:00 JST (対面式) 場所: 慶應義塾大学 三田キャンパス 開催概要 慶應義塾大学グローバルリサーチインスティテュート(KGRI) サイバー文明研究センター(CCRC) サイバーセキュリティ研究センターは、第15回サイバーセキュリティ国際シンポジウムを慶應義塾大学三田キャンパスで開催する。 国際的なサイバーセキュリティの重要課題であるデジタル社会における国家安全保障、経済安全保障、社会保障について、地球上の人類文明、地政学的紛争、ランサムウェアの影響、サイバー技術や生成AIの負の利用、量子技術、宇宙、日常生活におけるデジタル技術などについて議論する。 本シンポジウムの目的は、重要な問題を議論するだけでなく、エネルギー、通信、輸送、金融、医療、水などの重要インフラを含むライフラインを保護するための実践的な行動を計画すると同時に、データドリブン型クラウドの重要インフラを確保することである。 これらの内容では、各国、地域、G7、G20間のサイバーセキュリティにおける格差や提携について議論し、格差に対処するための行動や、世界規模で信頼される多国間の官民連携を構築するための行動へとつなげていく。 日本では、能動的サイバー防御法のサイバーセキュリティ対策が重要である。 国家安全保障の分野では、国際情勢でハイブリッド攻撃や波及攻撃が続いている。 Five Eyes、AUKUS、Quad、NATOなど複数の二国間・多国間組織が、国家安全保障上の課題として取り組んでいる。 各国が国家安全保障戦略を固めつつある中、日本でも積極的な防衛態勢が整いつつある。 経済安全保障の分野では、民間企業は、レジリエンスがあり、安全でセキュアな重要インフラとグローバルな供給を国際的に行うための重要なプレーヤーである。 グローバルなサプライチェーン、管理された非機密情報を含むセキュリティクリアランス制度、国や地域によって異なるリスクカテゴリーレベルやセクターを考慮すると、国家サイバーセキュリティ戦略と官民連携による協調評価が必要である。 社会保障の分野では、「信頼のあるデータ・フリー・フロー(DFFT)」を達成するための国際相互承認が重要であり、G7とG20が支持する「官民デジタルパートナーシップのための国際協定(IAP)」が確立した。 さらに、国や地域ごとの個人情報保護法は、市民や主要な意思決定者のプライバシーにとって重要である。データ利用とデータ保護のバランスが重要である。 サイバーセキュリティに関するこれら3つの主要な側面から、シンポジウムを通して主要な講演者やパネリストを招聘する。 私たちの議論は、政府、産業界、学術界の包括的で透明性のある国際的な多国間行動である。 プログラム オンライン登録とプログラムはこちら ホストのスピーチ:村井純(慶應義塾大学)、The MITRE Corporation 基調講演者およびパネリスト(招待):日本政府閣僚、各国大使、および米国、英国、EU、オーストラリア、フランス、インド、シンガポール、インドネシア、ドイツ、オランダ、エストニア、リトアニア、国連、経団連、大手企業、元・現国家安全保障担当幹部、INCS-CoE学術幹部からのVIP。 *プログラム内容は予告なく変更される場合があります。 会場 慶應義塾大学 三田キャンパス 主催者 慶應義塾大学KGRI CCRCサイバーセキュリティ研究センター The MITRE Corporation 後援(調整中) 米国大使館、英国大使館、欧州連合代表部、オーストラリア大使館、フランス大使館、ドイツ大使館、オランダ大使館、日本政府各省庁、AFCEA、BSA、INCS-CoE専門家など。 登録料 無料 お問い合わせ サイバーセキュリティ国際シンポジウム事務局 (株式会社イーサイド内) Mail: cysec-lab-event@sfc.keio.ac.jp オンライン登録とプログラムはこちら

※日本語の記事はこちら。 15th International Cybersecurity Symposium "Cybersecurity for Digitized National Security, Economic Security, and Societal Security: Global Multilateral Public-Private Partnership Actions" Hosted by Cyber Security Research Center of Keio University, The MITRE Corporation October 28 (Tue), 29 (Wed), 30 (Thu) & 31 (Fri), 2025 9:00-18:00 JST (In-person) Keio University, Mita Campus, Tokyo, Japan Overview We invite you to join us for the 15th International Cybersecurity Symposium at Cyber Security Research Center of Keio University's Mita Campus in Tokyo. We continue discussing towards actions on our key issues in international cybersecurity, namely Digitized National Security, Economic Security, and Societal Security, discussing our planet’s human civilization, geopolitical conflicts, ransomware impacts, negative use of cyber and generative AI, quantum technologies, outer space, and digital technologies in our daily lives. The goal of the Symposium is to not only discuss critical issues but also plan for practical actions to protect our lifeline including critical infrastructure such as Energy, Communication, Transportation, Financial, Healthcare, Water, while ensuring critical information infrastructure including clouds with data. The discussions will include the gaps and alliances in cybersecurity among countries, regions, G7, G20, and moving to actions to address the gaps and create trusted multilateral Public-Private Partnerships in global scale. In Japan, Cybersecurity is important adopting Active Cyber Defense law. In the National Security domain, we observe geopolitical tension continuously hybrid and spill-over effects. Multiple bilateral and multilateral organizations, such as Five Eyes, AUKUS, Quad, and NATO, are addressing the National Security concerns. Given National Security Strategy are firming up by many countries, cybersecurity defense is actively prepared in Japan. In the Economic Security domains, private sector companies are key players for resilient, safe, and secure critical infrastructure and the global supply chain internationally. Security Clearance schemes including Controlled Unclassified Information, the risk category levels, and designated sectors are different by countries and regions, so that coordinated assessments with Public-Private Partnerships are needed with National Cybersecurity Strategy. In the Societal Security domain, Data Free Flow with Trust (DFFT) is important transaction and cybersecurity themes for achieving International Mutual Recognition. Therefore, in the G7 and G20, Institute Agreement for Partnership (IAP) was launched. Further, the Personal Information Protection laws by country and region are significant for privacy of citizens and major decision-makers. It is important to balance between Data Use and Data Protection. With those three major aspects of cybersecurity, we invite key speakers and panelists throughout the Symposium. Our discussions are inclusive and transparent international multilateral actions among government, industry, and academia. Program Online registration and programs are here Host Speeches: Jun Murai (Keio), MITRE Keynote Speakers & Panelists (invited): Japanese government minister level, Ambassador level and VIPs from U.S., UK, EU, Australia, France, India, Singapore, Indonesia, Germany, Netherlands, Estonia, Lithuania, United Nations, Keidanren, major corporations, former and current National Security executives, and INCS-CoE academic executives. *program content is subject to change without notice Venue Keio University, Mita Campus, Tokyo, Japan Host Cyber Security Research Center of Keio University, The MITRE Corporation Supporters (in progress) U.S. Embassy, British Embassy, Delegation of the European Union, Australian Embassy, Embassy of France, German Embassy, Netherlands Embassy, Japanese government agencies, AFCEA, BSA, INCS-CoE experts, etc. Registration Fee Free Contact Information International Cybersecurity Symposium Secretariat(c/o e-side, inc.) Mail: cysec-lab-event@sfc.keio.ac.jp Online registration and programs are here

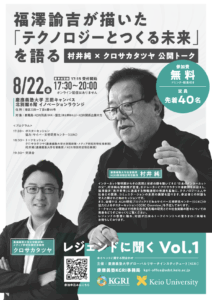

【開催案内】KGRI主催 レジェンドに聞く Vol.1:福澤諭吉が描いた 「テクノロジーとつくる未来」を語る(2025.8.22開催) CCRCから村井純とクロサカタツヤが登壇し、福澤諭吉『西洋事情』に通底する情報通信の発達を基軸に、テクノロジーと人や社会との関係、コミュニケーションの未来の展望を語ります。 会場では、ポスターセッション「CCRC Overview」を予定しております。 ※定員に達しましたので、参加登録は締め切らせていただきました。たくさんのお申し込みありがとうございました。 詳細はこちら ・主 催:慶應義塾大学グローバルリサーチインスティテュート(KGRI) ・日 時:2025年8月22日(金)17:30~20:00 (開場17:15) ・会 場:慶應義塾大学 三田キャンパス 北別館6階 イノベーションラウンジ 〒108-0073 東京都港区三⽥⼀丁⽬4番65号 https://www.kgri.keio.ac.jp/docs/access_kitabekkan.pdf ※北別館は三田キャンパスから北西に徒歩7分ほどの三田一丁目の高台に今年3月、新たに建設された施設です。 ・対 象:学内教職員、KGRI所員(塾外)、塾生(修士課程以上)、KGRI関係企業の方 ※要事前登録 ・参加費:無料(ドリンク・軽食付き) ・プログラム:17:30~ 村井教授の最新研究に関するポスターセッション「CCRC Overview」 協力:サイバー文明研究センター (CCRC) 18:30~ トークセッション 聞き手:クロサカタツヤ(慶應義塾大学大学院 政策・メディア研究科特任准教授) 村井純(慶應義塾大学名誉教授/KGRI特別特区特任教授) 19:30~ 交流会 ※本イベントのZoom配信はありません。

*日本語の記事はこちら *Click here for the first half of the event report. Panel Discussion: “Healthcare and Medicine Premised on AI” Moderator: Jun Murai — Co‑Director, Cyber Civilization Research Center, Keio University KGRI Panelists: Shigeru Omi — Chairman, Japan Anti‑Tuberculosis Association Yukio Yuzawa — President, Fujita Health University Rami Suzuki — President & CEO, ARC Therapies Inc. Hiroshi Asai (online) — VP of Infrastructure Strategy, Preferred Networks, Inc. Tatsuhiko Yamamoto — Professor, Law School, Keio University Masahiro Hashimoto — Lecturer, Department of Radiology, Keio University School of Medicine Koichi Hashida — Group Director, RIKEN Center for Advanced Intelligence Project (AIP) Center Shin Suzuki — Co-founder & Chief Development Officer, CureApp, Inc. / Medical Doctor Munenori Fukunishi — Global Program Director, Anout Co., Ltd. ◯ Murai: Today’s theme is “Healthcare and Medicine in the Age of AI.” The issue I feel most strongly about is that these technologies are something we have spent many years developing from the researchers' and engineers' side. With the experience of the pandemic, public understanding has grown, and the technologies themselves have undergone rapid evolution. I believe we are finally at a point where the ideals we once envisioned are becoming a reality that can be shared across society. In such a critical domain as healthcare and medicine, if we are unable to utilize these technologies, then, as someone who has been involved in their development, I can’t help but wonder what all our efforts have been for. At the same time, from the perspective of those working in healthcare, it seems that the environment is finally ready to make these long-held dreams a reality. Whether we view it from the standpoint of technology developers or within the healthcare field, I believe we have reached a point where we can no longer make excuses for the advancement of better medicine. To begin, I’d like to ask Dr. Hashida about the current state of AI. Dr. Hashida has been a leading researcher in this field for many years and has played a pivotal role in AI research in Japan since its inception. How do you see the situation as of 2025? ◯ Hashida: It's been about three years since the advent of ChatGPT, and from observing the developments since then, I feel that research has progressed more than I expected. However, regarding so-called 'Artificial General Intelligence (AGI),' I think we cannot achieve it simply by advancing current AI technology. Even if we were to extend today's deep neural networks, I believe we cannot create an entity that surpasses human intelligence. Current AI demonstrates immense power in superficial information processing tasks such as summarization and translation. Still, it does not possess abilities equivalent to human critical thinking, and as of now, there is no technological roadmap to achieve that level. ◯ Asai (Online) As Professor Hashida said, there are still many steps to go before we reach AGI. That said, the advent of Transformer models has enabled the more efficient use of computing resources, and I acknowledge that the performance of AI has steadily improved. In particular, tools like ChatGPT, which anyone can use through a natural interface, represent a significant breakthrough. We can now interact with AI through natural language or voice. I believe these changes in interaction indicate that AI is reaching a point where it could become a foundational part of our daily lives and work. ◯ Murai So far, we've been discussing the current state of AI from a technological perspective. However, in actual clinical settings, when we attempt to incorporate this technology, we encounter a range of challenges. Fujita Health University has taken on the challenge of adopting the latest technologies, including artificial intelligence. Dr. Yuzawa, from the standpoint of someone working in a hospital setting, what is your view on where AI currently stands? ◯ Yuzawa From my perspective, we are in a phase where we need to implement AI in society in a solid, practical way—mainly to support clinical care and research. As a university and hospital, we have a responsibility to fully utilize AI in clinical research, education, and research support, and to ensure its integration into society. And to utilize AI operationally, a fundamental assumption must be made that medical data can be repurposed for secondary use. At our hospital, the president carefully explains to all department heads why we are promoting AI and medical digital transformation (DX), and has built a system that enables all departments to work together. Without this, we would not have the foundation for using AI within a university or hospital. In this regard, I feel that our organizational governance is functioning well under the president’s leadership. Additionally, in the area of clinical trials, I believe the use of synthetic data opens up new possibilities for research into rare diseases, areas where real-world data has traditionally been hard to obtain. ◯ Hashimoto At Keio, we haven't yet been able to achieve the kind of institution-wide effort you described at Fujita Health University—for example, in generating discharge summaries. Currently, the initiative is being led by individuals who take the lead themselves, experimenting with prompts and promoting the use of AI more spontaneously. Getting everyone moving in the same direction remains quite challenging. That said, I believe our fundamental guiding principles for implementing AI are to reduce the burden on healthcare workers and to deliver benefits to patients. ◯ Murai Earlier, Professor Yamamoto spoke about the concepts of the "individual domain" and the "collective domain." I found that framework to be critical when considering how we perceive personal information. It seems to me that, because the Personal Information Protection Law was bound by the notion of the individual domain alone, it may have unintentionally closed off future possibilities for utilizing medical data. Is this way of thinking—of distinguishing between the individual and collective domains—something that is becoming accepted as an international standard? ◯ Yamamoto Regarding the EU's approach, I think there is a fundamental idea that information directly related to an individual should be under the control of that individual. This relates to concepts such as data portability rights. On the other hand, information that doesn't immediately or directly affect the individual—data that isn't tangibly returned to the individual—is treated as part of the "collective domain." The EU also promotes the proactive use of such data, including industrial data, as a public resource. Thus, I think the EU has made a certain degree of progress in clarifying this distinction and applying it effectively. In contrast, in Japan, discussions have often proceeded without sufficient awareness of these distinctions, which I think has led to various misunderstandings. For example, some people treat even "collective domain" data as part of the "individual domain," believing that every use must require individual consent. Conversely, some in the healthcare field, eager to use real data, tend to treat "individual domain" data as if it were a public resource. Since both sides have been engaging in discussions without clear distinctions, I suspect we have failed to establish sufficient 'trust' in the process. ◯ Murai In 2016, Japan enacted the Basic Act on the Advancement of Public and Private Sector Data Utilization. The law was intended to promote the use of collective data, but in practice, it hasn't functioned effectively. I’d like to ask you why it hasn't worked? ◯ Yamamoto It is just my personal opinion, but I think Japan’s Act on the Protection of Personal Information has often been criticized as being both “excessive and inadequate.” In other words, it fails to protect what truly needs protection, while overprotecting less critical information. As a result, it has grown in a somewhat grotesque and unbalanced way. ◯ Murai The Basic Act on the Advancement of Public and Private Sector Data Utilization ultimately became a parliamentary bill, not driven by any particular government ministry, which perhaps reflected a broader lack of leadership (in contrast to the typical Japanese legislative process, where government ministries and bureaucrats usually take the lead). With advancements in devices, we're now entering an era where even AI processing can happen on the user side, using personal devices. Against that backdrop, I'd like to ask Mr. Shin Suzuki: How do you view the relationship between personal data (individual domain) and societal data (collective domain)? ◯ Shin Suzuki I think we should distinguish medical data and lifestyle data. For instance, the information handled by therapeutic apps encompasses a range of data from the “bio-psycho-social” spectrum. Lifestyle data details, such as whether someone works in the morning or has a regular walking habit, are all crucial in treatment contexts. And I believe such lifestyle-related information should be stored on edge devices and used to inform personalized advice. In contrast, medical or biological data should be appropriately fed back and used to advance the field of medicine. ◯ Murai Changing topics slightly—Mr. Fukunishi is developing AI technology for surgical image interpretation to support robotic surgery. Could you briefly introduce yourself and tell us how far this technology has come? ◯ Fukunishi We’re working on developing AI for surgical support. Currently, minimally invasive treatments—such as robotic and laparoscopic surgery—are becoming more widespread, and Japanese surgeons are highly skilled, delivering very high-quality care. Nevertheless, the risk of complications cannot be eliminated. That’s why we’re working to develop technologies that can minimize such risks and ensure safe surgeries. As for Dr. Murai’s question about “Where is AI now?”, I believe AI development in the medical field is still in its early stages. For example, systems like SaMD (Software as a Medical Device) are only just starting to be established from a regulatory perspective, and legal frameworks surrounding the use of personal data are only beginning to take shape. ◯ Murai In robotic surgery, collecting and learning from operational data may one day enable the replication of expert surgeons' skills. I heard from Professors Ichiro Uyama and Koichi Suda from Fujita Health University about ‘surgical intelligence.’ In one of our earlier seminars, the question of who owns the surgical data from the da Vinci system was raised. It seems that Intuitive Surgical, the company behind the system, holds a massive amount of that data. Professor Matsumoto, what are your thoughts on this? ◯ Matsumoto Motion data from the Da Vinci robot’s joints and other components is sent to and analyzed by the company’s headquarters in the United States. It seems that even comparisons between surgeries performed by Dr. Uyama at Fujita Medical University and those by other surgeons are being conducted. However, I’m not sure how exactly that data is being used in practice. ◯ Murai In AI development, where the data resides is critically essential. If robotic technologies were to be developed within Japan, it would be of great significance. As Mr. Tanaka also mentioned earlier, I believe we need to enhance the value of domestically developed technologies. ◯ Yuzawa We’re having similar discussions. If AI can learn from the surgical logs of experienced doctors, it may be possible for other surgeons to learn easily and replicate those high-level skills. But then, who owns the rights to that technology? Currently, the rights belong to the companies, but I question whether that’s appropriate. We need to protect the rights of universities and physicians and ensure that these are reflected in future development. As part of academia, it’s also vital that we speak out on these issues. ◯ Yamamoto There’s also what I explained as a “responsibility sponge” issue in the medical field. When an accident occurs, companies often want to avoid liability, so they place doctors in formal positions for them to absorb that responsibility. However, there are cases where doctors cannot immediately intervene, and their presence may ultimately serve only as a liability buffer. This poses a threat to the dignity of physicians, and we need to redesign the frameworks for risk-sharing and responsibility. ◯ Murai The question of where responsibility lies is a tough one. After a device is connected to the Internet, product liability (PL) law alone is no longer sufficient. This issue also ties closely to intellectual property (IP). Determining who bears the product liability becomes critically important. Whether that “responsibility sponge” role is played by insurance or another system is something we’ll need to resolve going forward. ◯ Omi As mentioned earlier in the presentation, the emergence of AI has created a structure in which humans are forced to act as buffers. AI, which is intended to serve humans, ultimately places more burdens and responsibilities on us. This is not only a legal issue, but also one that reflects deeper human value systems, making it a very complex and challenging problem. ◯ Murai One of the most critical domains for the application of AI in society is healthcare. Challenges resolved in this area will likely have significant social applicability in other fields as well. To move forward, collaboration among diverse stakeholders—such as the healthcare industry, universities, research institutions, and the government—is crucial. Within the context of digital policy, we are constantly required to develop mechanisms that connect these different sectors horizontally, particularly in a society that is often siloed. In other words, what’s needed is the construction of a new model of governance. I’d like to ask Professor Hashida, do you have thoughts on the roles and responsibilities of the various stakeholders involved in AI and healthcare? ◯ Hashida From now on, interaction with AI will become the core of the user interface. AI will serve as an intermediary, connecting users with services. As a result, traditional apps and websites will gradually disappear, and in every industry, customer touchpoints will be replaced by AI. I believe this shift will begin particularly with small- and medium-sized enterprises. However, fields such as education and healthcare do not change easily. Connecting these domains to personal AI systems will likely emerge as a significant challenge in the years to come. ◯ Murai Dr. Omi and Dr. Kurokawa have both played key roles within the government, and based on that invaluable experience, I would very much like to hear your thoughts on how we should move forward from here. ◯ Omi I propose establishing a long-term, open forum that engages all stakeholders to foster a collaborative environment. I hope that the experts gathered here today will play a central role in leading such a platform. What I believe Japan must learn—based on my experience at the WHO—is the importance of a process for thoroughly organizing and documenting both what has already been agreed upon and what remains unresolved when dealing with complex, long-term issues. This documentation must then be shared. Also crucial is the role of "translators" who can clearly convey technical terms in understandable language. Besides, we must also consider people's emotions and feelings. Japanese society tends to operate in short bursts, having one heated discussion and then letting it cool off quickly. However, we need to address these issues over a 5–10 year span. I believe that such careful, ongoing dialogue is precisely what is required as we build a society that integrates AI. Again, we also need people who can serve as translators or facilitators between the various parts. ◯ Kurokawa Physicians are indispensable, and the structure of healthcare systems varies from country to country. Japan has a unique system where people are free to choose their hospitals, and much of the system is supported by public funds. However, with the aging population and declining birthrate, we must now reconsider whether this model is sustainable. ◯ Murai Based on your comments, it is clear that there are limits to continuing with the current healthcare model. While reforming entrenched interests remains a major challenge, we have seen in the relatively short history of the Internet that technologies with broad public support can advance rapidly, sometimes even surpassing existing systems. And what is crucial now is to build social consensus carefully and strategically. ◯ Yamamoto When it comes to building “trust,” the social atmosphere is even more important than legal frameworks. While AI excels at quantitative processing, it struggles with qualitative aspects, such as emotions and values, which carry uncertain risks and complexities. That’s why fostering trust through cross-disciplinary dialogue—spanning medicine, law, and philosophy—is so important. As Dr. Omi emphasized, the role of “dialogue” is crucial. A bottom-up social consensus is indispensable for the successful implementation of AI. ◯ Murai "Transparency" is just as important as "dialogue." It is critical to clarify which technologies are being used and how they impact people. In this context, "standardization" becomes essential. When technologies are standardized and widely adopted, transparency tends to increase. Moreover, costs tend to decrease, and the benefits can be more broadly distributed. In contrast, monopolization through patents risks driving prices up. Indeed, the Internet achieved low-cost access through "standardization". Similarly, I think "transparency" and "dialogue" in medical technology can foster "safety" and "trust," which in turn lead to broader adoption. With decades of experience in shaping the Internet, I'm very interested in how we can organize and understand the relationship between Japan's domestic or local space and the global or international space. For example, from the standpoint of rule-making, medicine is heavily influenced by national borders, whereas the Internet has evolved across them. As a result, we now have national spaces, such as healthcare, coexisting with global digital environments. Given that, we must ask: How can Japan's use of AI contribute globally? Is foreign-developed AI truly suited for Japan? We must rethink not only how data has been structured in the past context but also how Japan should shape its data practices moving forward. But to begin with, we need to think more deeply about the relationship between healthcare and health. Mr. Suzuki, how should we approach this? ◯ Shin Suzuki The connection between the fields of health and medicine is a highly compelling topic. In our products, areas such as smoking cessation and hypertension fall within the scope of prevention, and we aim to approach these issues from a broader concept of “health.” For this reason, we offer both medical devices and non-medical products designed for preventive purposes, utilizing the same approach. While society tends to draw a line between healthcare and medicine, we are particularly interested in the gray area that lies between the two. From a practical standpoint, medicine offers advantages for business development because medical institutions are widely established throughout the country. Once a product is approved within the national health insurance system, it can be deployed nationwide. In that sense, we believe there is significant value in medical device-based business models. At the same time, as seen in the health-focused services presented today by DeNA, other valuable approaches also play an important role, albeit in a different way. ◯ Murai In general, Japan’s medical system and the quality of its healthcare are often seen as a source of national pride. At the same time, as Dr. Kurokawa pointed out earlier, this system relies heavily on public funding—most notably through the universal health insurance system—and we are beginning to see its limitations. Still, I hold a strong belief that in this rapidly evolving landscape of health and medicine, Japan can make unique contributions, primarily through the integration of AI. If we can fully realize these strengths, I believe there is a path to expanding them globally and making a meaningful contribution to the world. Let's all discuss how such a movement might be nurtured and developed. ◯ Fukunishi Speaking from the perspective of AI in the field of surgery, I believe Japan has a significant strength. There’s no question that Japanese surgical procedures are highly meticulous. The quality of data generated from the medical field is extremely high, which is a significant advantage in applying AI. On the other hand, when we examine global deployment—especially in the field of health—cultural factors become profoundly influential, introducing added complexity. However, when it comes to more clinical and objective fields, such as medical devices, the structure of the human body is universal. International companies already dominate the global medical device market, and I believe we must step into that arena. Our company has a strong desire to take on the world, and we cannot afford to stand still. ◯ Shin Suzuki The field we’re working in, therapeutic apps, is heavily influenced by psychological and social factors. We initially aimed to expand into the U.S. market, but things didn’t go as smoothly as expected. For example, Japan is a high-context culture where language and cultural understanding are closely intertwined, making it easier to design treatments based on shared assumptions and values. In contrast, the U.S. is incredibly diverse in terms of race and culture, and we found it challenging to identify a shared cultural baseline among “Americans.” This experience made us realize just how deeply localized therapeutic apps should be, especially in domains where psychological and social factors are significant, and how difficult it is to scale them globally. ◯ Rami Suzuki Our clinical trials began in Japan, so it’s natural that our efforts are rooted here. In addition, I think we don’t necessarily need to draw a hard line between “health” and “illness.” On the contrary, I firmly believe that aspects of everyday life—such as mental health, diet, and sleep—are deeply intertwined with patients’ overall well-being and treatment outcomes. For example, some participants of our clinical trials even travel long distances to visit hospitals in Tokyo. However, I worry that receiving intense treatment after such a long journey could lower its effectiveness. ◯ Asai (Online) The LLM (Large Language Model) we are developing is focused on enhancing Japanese-language performance and uses a substantial amount of Japanese data. Globally, major LLM developments are centered in places like the United States and China; however, these global models often fail to reflect local cultural contexts accurately. Even if the interface is standardized worldwide, the foundation model frequently skews toward English- or Chinese-language thought patterns. This makes us acutely aware of the need to build models, especially for medical data, that are rooted in local cultural contexts. Moreover, different countries have different views and regulations regarding AI training. Ensuring transparency and accountability, given these disparities, is key to creating a foundation model that people feel comfortable contributing their data to. ◯ Murai To close, I’d like to ask each of you: based on today’s discussion, what will you personally commit to doing next? ◯ Fukunishi The digital transformation of the surgical field is undoubtedly a significant challenge, but even as our field continues to evolve, we’re committed to making a global impact. We genuinely want to go global, and we’re working hard with that goal in mind. I’d be very grateful for your support and guidance. ◯ Shin Suzuki I want to create applications that are truly native to generative AI. As Professor Hashida mentioned, AI interfaces will likely become standardized in the future. In such a world, therapeutic apps could also be modularized, where only the algorithmic parts require approval, while the interface design remains open for customization. Anticipating that future, I aim to develop new, dialogue-based therapeutic applications. ◯ Hashida As Murai-sensei pointed out, while medical systems are national in scope, the Internet, data, and algorithms are inherently global in nature. I believe that by harnessing the power of the Internet, cross-border medical services could become a reality. Some countries have laws that restrict the cross-border transfer of medical data, but these laws typically apply to businesses, rather than individuals. If individuals retain control over their own data, they could take it to another country and receive treatment there. As I mentioned earlier, we are currently working in partnership with local governments. This is because municipalities don’t monopolize resident data, making it easier to develop decentralized services. ◯ Hashimoto Large Language Models (LLMs) are potent tools, and I believe they hold immense potential in addressing the looming issue of workforce shortages in healthcare. However, effectively integrating such tools into medical settings requires entirely new rules and frameworks. It should be very different from those we’ve used for conventional technologies. With many stakeholders involved, I hope to personally contribute to shaping these new rules. ◯ Yamamoto In the context of co-creative rule-making about new technology involving multiple stakeholders, those of us working in the legal field are often seen as the ones who “apply the brakes.” But that’s not our intention. By engaging in dialogue from the earliest stages of development, we aim to be true partners, helping to accelerate progress in the right direction. ◯ Rami Suzuki Today’s discussion has deepened my commitment to the goal of early detection and complete cure of cancer. I feel strongly that we must accelerate our efforts, and I will do everything in my power to deliver results from Japan that will be remembered in history, living up to the expectations Professor Murai has expressed. ◯ Yuzawa Today’s discussion has reaffirmed the need for universities to play a leading role in advancing research and development for next-generation healthcare, including medical DX and the use of AI. In the future, we aim to promote medical digital transformation and facilitate smoother international data collaboration. One of Japan’s greatest strengths lies in its extensive health screening data, a result of its super-aged society. We aim to leverage this data to inform future health forecasting. Additionally, in the field of disaster medicine, we must prepare for large-scale events, such as a potential Nankai Trough earthquake. We must establish systems, through the Ministry of Health’s shared electronic medical record service, that allow essential medical data to be accessed anywhere. ◯ Omi We’re living in a time when society is increasingly fragmented, making it harder for everyone to move in the same direction. That’s precisely why we need more than just rule-making; we need empathy and the true meaning of dialogue. Therefore, not just among IT experts, we need deeper conversations involving people from all fields. Finally, regarding my hopes for Japan: I genuinely believe that Japan can become a global leader, not in terms of military or economic power, but in global health. Many countries place their trust in Japan. Suppose we can translate discussions like today’s into simpler, more accessible language and share them with the world. In that case, I believe we can contribute not only through culture but also to the global economy as a whole. ◯ Asai (Online) As Professor Murai noted, standardization is absolutely crucial in the context of applying AI technology to society. As an engineer, I aim to develop technical standards, such as protocols and mechanisms, that can accommodate a diverse range of policies and regulatory frameworks. This is the kind of standardization I want to contribute to through my work. (written by Hitomi Sano, photo by Shun Arima) *Click here for the first half of the event report. For previous articles, please refer to the link below: Aug 18, 2022 【Event Report】The 1st Medical and Health DX Seminar Nov 10, 2022 【Event Report①】The 2nd Medical and Health DX Seminar 【Event Report②】The 2nd Medical and Health DX Seminar Jun 19, 2023 【Event Report①】The 3rd Medical and Health DX Seminar 【Event Report②】The 3rd Medical and Health DX Seminar